As a supporter of human rights, the World Bank will have a difficult decision to make if Ghana enacts the harsh anti-LGBTQ bill that Parliament approved in February. That’s how the international finance behemoth views the situation — as a question for the future, when it may need to weigh the importance of rescuing Ghana from economic troubles vs. the importance of opposing the cruel homophobic legislation currently awaiting action by the Supreme Court and President.

But that’s not how human rights advocates view the situation. They are calling on the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to speak out now and warn Ghana that allowing the bill to become a law would likely lead to Ghana losing $3.8 billion in funds from the World Bank and $3 billion from the IMF.

Elana Berger, executive director of the Bank Information Center, a charity that campaigns for better transparency, accountability and inclusion in development finance, said the World Bank was in a unique position to “persuade Ghana to reconsider” with the prospect of losing its promised $3.8bn (£3bn) of funding.

“We believe that everything the World Bank does should be moral, fair and inclusive,” she said. “Funding a country with this law will lead to discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. We’re not anti the World Bank, but it can do a lot more to improve the inclusion of its projects.”

Rights vs Funding

To borrow from the World Bank, countries must commit to respect “environmental and social standards” that protect communities from harm and exclusion in projects the lender finances. Where there’s a risk of these standards not being met, the borrower has to put in place mitigation measures to prove that authorities are still able to implement the projects in a way that isn’t discriminatory or harmful.

But anti-LGBTQ laws would elevate that risk, according to the World Bank’s anti-discrimination guidelines.

“To what extent can we negotiate the lives of people” said Alex Kofi Donkor, the director of the activist group LGBT+ Rights Ghana. “The only option is for the bill to be struck down.”

Supporters say the legislation — passed in February — is necessary to address gaps in a colonial-era law that already bans gay sex in Ghana, but which has been widely ignored for decades. It hasn’t generated as many international headlines as the measures in Uganda, originally introduced in 2014, which were subsequently revoked after an international clamor including the suspension of a World Bank loan. Uganda’s version grabbed global attention by prescribing the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality” for certain offenses. Having same-sex relations in Uganda carries a penalty of as much as life in prison, but identifying as homosexual isn’t itself criminal.

“The Ugandan law targets LGBTQ people in such a horrible way,” said Donkor. “But the Ghanaian bill goes even further. Even the family members of LGBTQ persons could go to prison if they don’t report them. That’s why we keep reiterating how extreme this bill is.”

The legislation appears to borrow from Nigeria, which outlawed civil society organizations that support LGBTQ groups in 2014, and from Uganda which drastically increased prison penalties. But it also draws from Russia by criminalizing speech, Hungary by preventing LGBTQ education and Saudi Arabia by targeting content providers which could extend to streaming services like Netflix Inc., said Kristopher Velasco, an assistant professor in the department of sociology at Princeton University.

“Other countries have one piece of the bill,” said Velasco, “Ghana pulls all of them together into one dramatic legislation.”

Sovereignty Struggles

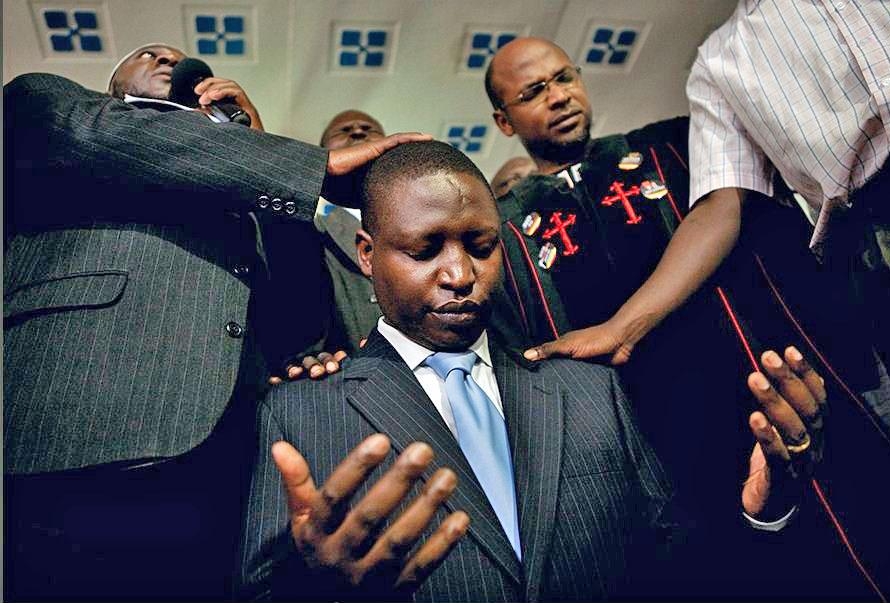

Anti-LGBTQ activists are looking to coordinate efforts across the continent. At Uganda’s Imperial Resort Beach Hotel, overlooking Lake Victoria and a short drive from the country’s main airport in Entebbe, Sarah Opendi, Uganda’s minister of state for mineral development, took the stage last week to welcome parliamentarians from Ghana, Comoros, Zambia, Ethiopia, Kenya and beyond to the second African Inter-Parliamentary Conference on Family Values and Sovereignty.

The gathering emphasized the perceived conflict between international lending standards and family values. And hinted at the possibility of clashes between some governments and lenders.

“For decades, international institutions and donor countries have been providing substantial, much-needed foreign aid to address the multi-faceted needs of our countries,” a promotional note read. “However, along with this support, have often come requirements to implement policies and programs, which directly impact our national sovereignty, African culture, family values, and Africa’s children.”

David Bahati, Uganda’s state minister for trade who introduced the original anti-LGBTQ bill in 2014, told the conference of the danger that “we are going to continue to be bullied, we are going to continue to be manipulated, we are going to continue to be influenced” — a possible reference to Uganda’s treatment after it pushed forward with its legislation last year.

“Poverty is one of the things that weakens our fight in our defense for family values and cultural values,” Bahati told delegates.

Those comments come against a backdrop of sub-Saharan Africa facing an “acute” funding squeeze, according to the IMF. Borrowing costs are high, spurred by the US Federal Reserve’s monetary policy that kept global financing conditions tight. Some of the countries that sold eurobond debt when financing was cheaper are now spending a bigger chunk of their revenues on interest payments.

Ghana went into default in December 2022, and sought a $3 billion bailout from the IMF and additional support from the World Bank. Zambia and Ethiopia also defaulted. Other countries are having to cut spending on healthcare and education to keep up with debt repayments. They are also turning to concessional lenders like the World Bank and IMF to borrow at cheaper rates than those available on the international and domestic capital markets.

Demand for such financing outstrips supply, in theory giving lenders leverage over governments. Rights advocates have successfully encouraged institutions like the World Bank to spell out that sexual orientation and gender identity, or SOGI, is considered a non-discrimination category. That language has caused much unease in some conservative circles, including a growing number in African parliaments.

The World Bank has long had non-discrimination standards covering marginalized groups, but the development of a policy specific to SOGI was created in the wake of Uganda’s 2014 bill, said Fabrice Houdart, who was president of GLOBE, a resource group for LGBTQ employees of the World Bank, at the time. It was the first time the World Bank suspended loans for violating social standards on the basis of discrimination against sexual and gender minorities, he said.

“It seemed more like a capricious move in 2014. There were no proper consultations. Even LGBT groups weren’t consulted,” said Houdart. “The Bank’s stand against Uganda in 2023 was very different,” he said. “It was rooted in policy.”

‘Global Interference’

The Entebbe conference showed how organized the opposition to the institutionalization of LGBTQ rights has become, using the argument of national sovereignty.

“The irony is that a lot of anti-LGBTQ policy is tied to global interference,” said Velasco. “Globally, the pro-family movement, which is largely led by the US, has other things they are working on, including issues about women’s health, such as abortion and contraception. They’re against anything that limits procreation,” he added. “They’re very worried about fertility rates.”

The family values movement defines family as a unit created from the union of a man and a woman, and sees broader definitions of family as a threat to population growth, making LGBTQ groups a target of their advocacy work, said critics. Sam George, the main sponsor of the Ghanaian bill, has attended at least two “pro-family” conferences in the US, organized by conservative Christian groups that promote the “natural family” and push an anti-LGBTQ agenda.

The UN’s Abani urges caution however over next steps for both the government in Accra and the international institutions. Sanctions, he says, should be a conversation of “last resort,” because it risks “stoking sentiments in favor of the bill in an election year.”

In Uganda, sanctions were the “real” reason why the 2014 law was repealed, argued Clare Byarugaba, a coordinator at Chapter Four Uganda, a rights advocacy group which has urged the World Bank to maintain its position on the country until the law is repealed.

“We got to a point where we had nothing left to lose and it was the only tool that worked,” she said. “We are sharing the strategies we’ve used over the last 10 years in Uganda with Ghanaian activists.”

The Hoima Post – Trustable News 24 -7

The Hoima Post – Trustable News 24 -7